My Opinion | 128690 Views | Aug 14,2021

Mar 23 , 2025

By Jim O’Neill

The ramifications of a softening US economy ripple through financial markets. Analysts closely watch indicators like the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's GDPNOw tracker, forecasting negative growth for early 2025 and raising concerns, writes Jim O'Neill, a former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management and a former UK Treasury minister. In this commentary provided by Project Syndicate (PS), he argued that the dramatic rise in inflation expectations, reaching historic highs not seen in over three decades, should catch attention.

Although I no longer live and breathe the markets on a daily basis, I have never forgotten some key lessons I learned early on as an economist working in the financial industry: it is much easier to be wrong than right.

Consider one of the big, early surprises of 2025. Late last year, following Donald Trump's election victory, the US Dollar was steadily rising, reflecting widespread expectations of relatively robust US economic growth, additional fiscal stimulus, and new or somewhat higher tariffs that supposedly would strengthen the dollar further. Instead, the dollar has been declining sharply.

Something else I learned early on is that given the size and depth of the foreign exchange market – where all known information gets priced in very quickly – it pays to be sceptical of overwhelming consensus views. Often, some element of the consensus outlook proves rather questionable. For example, I found it odd that so many forecasters saw tariffs as pro-dollar and unlikely to be overly disruptive to the US economy, despite being a net negative for US consumers.

Then there is the fact that some of Trump's closest economic advisers have spoken openly about the need for other currencies to be stronger. That is why they have been pushing some new version of the famous 1985 Plaza Accord, whereby Japan and Germany agreed to strengthen their own currencies against the dollar to placate the United States. The "Mar-a-Lago Accord" is supposed to do the same.

What seems clear to me is that the Trump Administration is focused on US manufacturing and its own definition of competitiveness, neither of which offers much basis for expecting a persistently strengthening dollar. True, the usual counter-argument is that tariffs are needed because the dollar's strengthening cannot be stopped, given the "exceptional" US economy's unrivalled merits. America is "exceptional." It boasts deep, liquid financial markets and cutting-edge technology, and it is preeminent in security matters and superior to its peers in terms of overall growth.

If the dollar's relative weakness in 2025 is merely a price correction, these fashionable arguments will likely re-appear and carry it upward again. And yet, there are cyclical, structural, and even systemic factors that may make continued dollar weakening more likely.

On the cyclical front, recent high-frequency data point to a near-term softening of the US economy, with the closely watched Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's GDPNOw tracker forecasting negative growth for the first quarter of this year. Of course, it is too early to know whether this will be borne out. But, while it could be simply a temporary or technical artefact of the data, it is hardly the only warning sign. The latest business and consumer confidence surveys also give cause for concern.

Even people outside of the financial industry are becoming more unsettled about future inflation. The latest University of Michigan five-year inflation expectations survey (one of my own favoured indicators) shows a rise to 3.9pc, the highest in more than 30 years. If this trend persists, watch out.

Some analysts argue that this index is not as reliable as it once was, owing to changes in the survey methodology and the suspicion that Democratic voters are more inclined than Republicans and independents to respond. But, professional pollsters know how to account for such discrepancies, and unless the actual calculation is somehow more biased toward Democrats, this argument is unconvincing.

Many more commentators are suddenly talking about US stagflation, and owing to Trump's erratic and aggressive behaviour. Other countries are not simply standing still. As I noted last month, policymakers in many countries – especially in Europe, but also in China – recognise that they must make changes to reduce their economies' dependence on the US.

All these developments in the US and globally can account for the dollar's recent decline. But, there is also a more fundamental issue apart from what might otherwise be a "cyclical" decline. If Trump persists with tariffs and they do raise US inflation and create knock-on effects in the real economy, the longer-term equilibrium value of the dollar is likely to be less than it might have been. This, too, would warrant an adjustment in the price of the greenback – and perhaps a rather large one, if Trump keeps doubling down on his current approach.

That brings us to the systemic dimension.

There is a long-running academic debate about why the dollar's strength has persisted for so long, with some arguing that its value goes hand in hand with US power as a security guarantor and the dominant player in the post-World War II multilateral institutions. If the US is now abandoning these roles, others will be forced to stand up for themselves, and the dollar's unquestioned dominance could finally come to an end.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 23, 2025 [ VOL

25 , NO

1299]

My Opinion | 128690 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 124938 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 123020 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 120834 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

May 3 , 2025

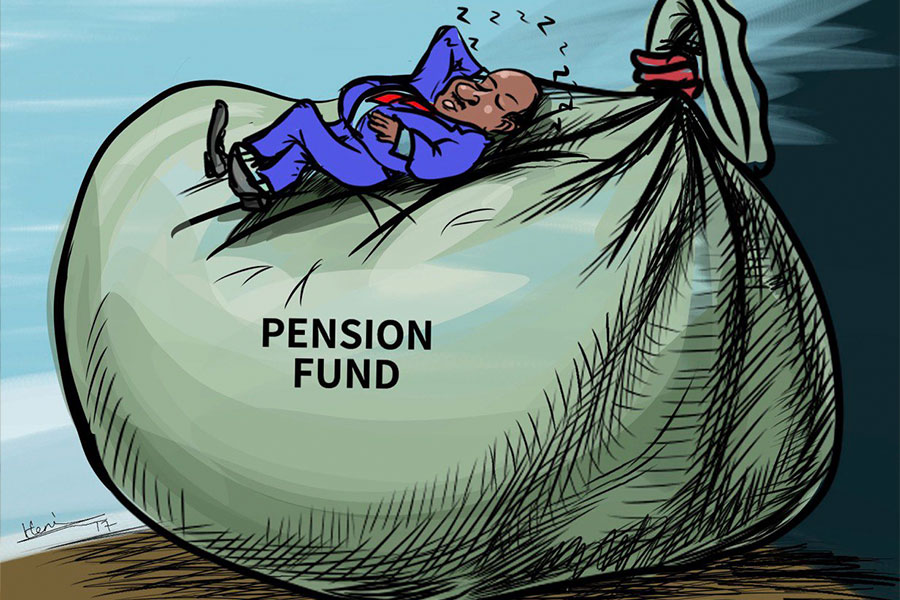

Pensioners have learned, rather painfully, the gulf between a figure on a passbook an...

Apr 26 , 2025

Benjamin Franklin famously quipped that “nothing is certain but death and taxes.�...

Apr 20 , 2025

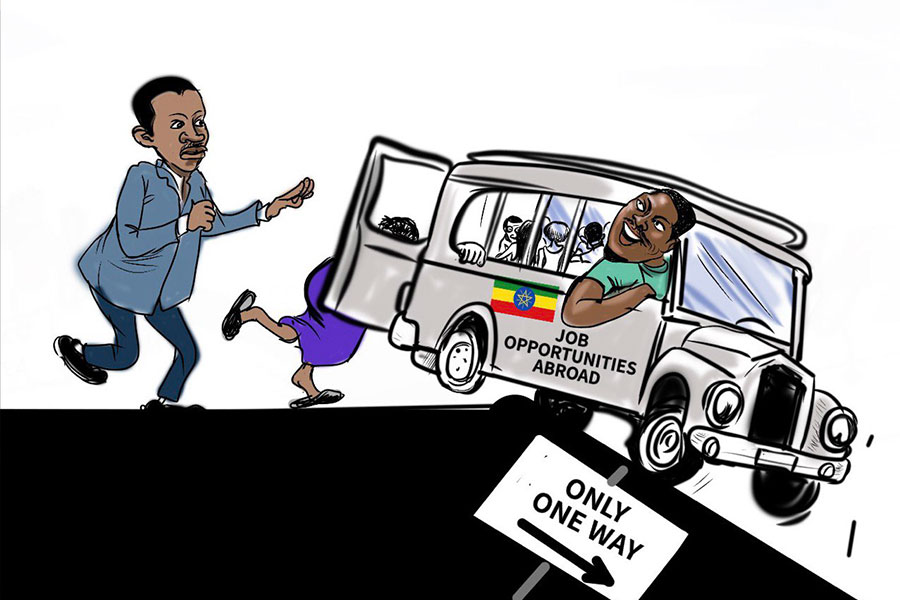

Mufariat Kamil, the minister of Labour & Skills, recently told Parliament that he...

Apr 13 , 2025

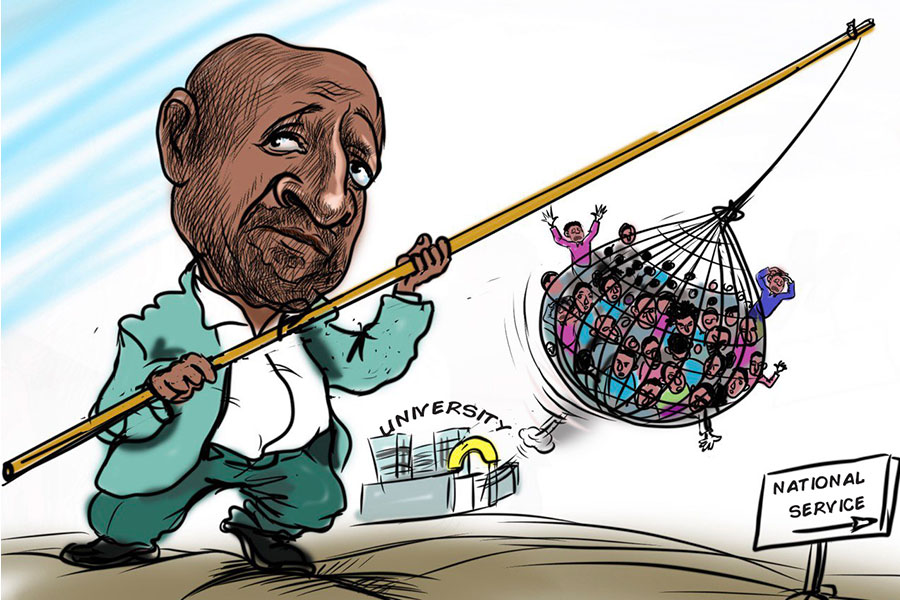

The federal government will soon require one year of national service from university...

May 3 , 2025

Oromia International Bank introduced a new digital fuel-payment app, "Milkii," allowi...

May 4 , 2025 . By AKSAH ITALO

Key Takeaways: Banks face new capital rules complying with Basel II/III intern...

May 4 , 2025

Pensioners face harsh economic realities, their retirement payments swiftly eroded by inflation and spiralling living costs. They struggle d...

May 7 , 2025

Key Takeaways Ethiopost's new document drafting services, initiated in partnership with DARS, aspir...